There’s the opening sequence of solos in which everyone gets a turn to present her or himself – a kind of introduction to the characters that we will be following for the coming hour and a half as they meet each other, face personal demons, and figure out their role in the larger world. It was there in Max as well and even there at the start of Sharon Eyal’s Bill.

There’s the deceptively simple set – a clean, solid wall in the back, similar to Hora and Three (this time white) – that serves to highlight the dancers and bring them closer to the audience while also seeming to imprison them, creating an immediate sense of claustrophobia and urgency while at the same time serving as a canvas on which to wash a spectrum of atmospheres.

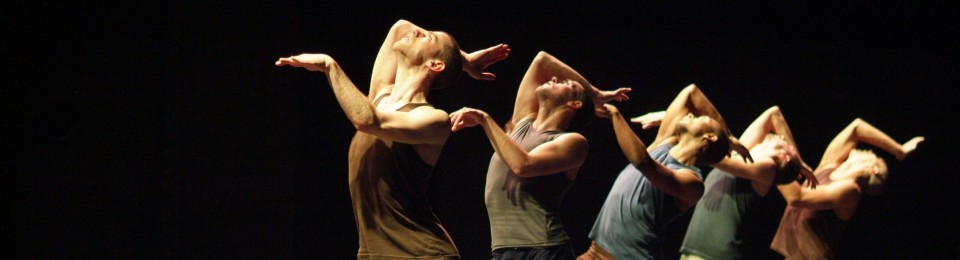

There’s the casual, pedestrian costumes – t-shirts and tank tops that span the rainbow (save for a scene of full and fantastic black gowns for the men) – and there’s the dramatic lighting – cold whites and warm yellows that shoot from the side and bounce off the white floor, turning the set itself into a light source, with a splash of color every once in a while.

And of course, there’s that movement – a marathon of unrelated gestures, each of which tells its own story, piled on one another like layers of memory that can make you smile or break your heart even if you don’t know why.

It’s all very Ohad, and all very Batsheva. The look and feel of the company has become entirely recognizable. But it’s precisely that familiarity that allows Sadeh21 to pack the punch it does.

For those who follow the company, there’s a sense of cohesiveness, of referencing past creations and merging them into one dramatic statement. Not like the quilt-like montages that Ohad has favored recently that splice scenes from earlier works together to create new monsters (Decadance, Project 5, Kyr/Zina), but rather a careful weaving of the visual motifs and aesthetic and aural interests that have been preoccupying Naharin for the past decade and giving birth to some of the most daring, sensitive, humorous, and poignant dance in the world.

And for those who don’t follow the company, who may be meeting Batsheva for the first time in this vast field (the English meaning of sadeh), one can only advise to lay back with arms clasped under head and gaze into the sky to conjure a guess at its morphing cloud formations and overwhelmingly expansive constellations of stars. In many ways, Naharin’s choreography is a similar game of connect-the-dots, giving you the three points of Orion’s belt and asking you to find the entire hunter around it.

Yet despite the sense of being welcomed into the known and recognizable world of Batsheva, Sadeh21 stands noticeably apart from its older brothers and sisters. Naharin’s work has always been theatrical; this one verges on the cinematic. Something about the scope of its intentions, or the power of so many bodies in motion, or the ease with which the work flows from one scene to the next despite sudden shifts in mood, gives the feeling of watching an expertly edited and exquisitely polished piece of film, simultaneously intimate and epic.

Or maybe it’s just the startling concluding scene that suddenly, literally, takes your gaze to a new level, one that has been there all along but you didn’t notice – and couldn’t know – its fatal purpose. As the dancers tumble from grace, swan dive into the abyss, and recklessly leap into the distance – only to climb back up and do it again – actual projected credits roll along the white wall, now bordering an empty stage, imprisoning no one.

And at this moment, a revelation that perhaps all along we have been watching life itself unfold. The search for identity, the birth of sexuality, the struggle for communication, the comfort of community, the pain of fighting against or rediscovering that identity, and the many ways in which it can all possibly end.

There is no curtain call, no bows. Because if there were, it would mean that this is just another performance, and we’re merely members of an audience, and life is something that only waits for us outside the theater. None of which is true.